Fears were raised about the increasing cost and the wisdom of building new lines in the northeastern states in India.

Five lines of 1.37 trillion rupee (15.64 billion US dollars) are built in the northeastern border states, but they face tremendous time and costs.

The Jiribam line, which is 110.6 km long, which was launched in 2003, was now targeted, while costs increased from 7.3 billion rupees to 250 billion rupees. The SIVOK line, which was approved in 2008, is expected to be completed in 2028, while the project costs increased from the original estimate of 13.4 billion rupees to 150 billion rupees. The DHANSIRI line 88.4 km, which was launched in 2006, is expected to be completed in 2030, while costs increased from 8.5 billion rupees to 140 billion rupees. The construction of the 108.4 -km Chilong line began in 2010, but it is unlikely to be completed before 2040, when the project is currently stopped due to the local opposition, and the costs of the project have increased from 40.8 billion rupees to 650 billion rupees.

It took 51.38 kilometers long, which received a safety permit from the Railways Safety Commissioner (CRS) before the opening of next month, 17 years old to build and witness an increase in cost from 6.2 billion rupees to 192 billion rupees.

“The real cost escalation is much higher, if inflationary costs are calculated on an annual basis,” says Alwlak Kumar Verma, chief of Indian railway engineer. Speaking to IRJ, Verma said that CRS approval on the Bairabi -Sarang line was awarded “in haste” and that “design defects” have been overlooked.

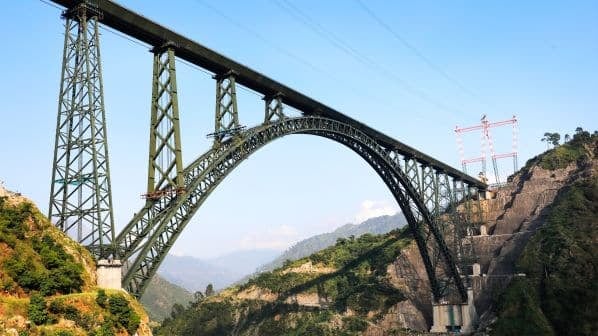

“The Bairabi -Sarang line extends through the uninhabited pelvic basins in the low terrain, however, 96 % of its length is 51.4 km in tunnels, high pieces, and bridges,” says Verma. It includes six bridges longer than 50 meters, including a 106 -meter column bridge.

Verma says that building massive bridges in the gentle hills was unwanted and will limit the speed of the train to crawl from 25 to 30 km/h.

In a post on the social media platform X, Verma said: “In order to maintain a flat gradient from 1 out of 80, these lines will be forced to embrace the valley floors, sculpting through soft colofium, slopes exposed to ground collapse, and floods.

Verma’s concerns appear to arise from the 2016 experience of the early opening of the Lumding – Silchar line in Assam. Within the first few months of the start of commercial operations, there were two travel and dozens of landslides, which led to the withdrawal of train services for three months. In 2022, the line was closed for 48 days. This year, the line has been closed on multiple occasions, including seven -day disorder after a major landslide.

Verma states that the decision of the Indian railway to adopt the stability of the slope by making excessive soil pieces in the unstable eastern terrain that receives annual rain from 2500 to 4000 mm may lead to catastrophic disasters in the future.